TL;DR: The gym is more than just a place to grunt and throw weights around. Apply tried and trusted scientific principles to your understanding and practice of weight room exercise, in order to see the best and quickest results.

Introduction

Welcome back, biohacker. Today we will be discussing various must-know techniques, tactics, and kinesiological principles to ensure that you get the gains you deserve when going to the gym. While this list will not be an exhaustive list detailing every single aspect out there, we will do our best here to break down some of the gym components necessary to maximize your time when hitting the weights. Finally, this article will focus primarily on weight training. If you are looking for an article on cardiovascular and/or other aerobic training please consult our Cardio Science 101 article HERE. With that said, let’s jump straight in by explaining the 3 main approaches to weight training. First up, we have:

Strength Training

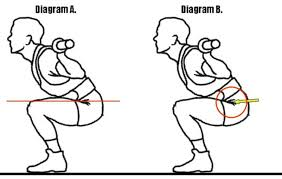

Strength training is usually some sort of powerlifting, Olympic lifting, or Strongman training. In all 3 of these approaches, the trainer attempts to get the body to become as strong as possible by training a few key compound lifts, which require multiple groups of muscles to work together. These exercises for powerlifting, for example, are the deadlift (lifting of weight directly off the ground and up beyond the knees), the bench press (lying flat on your back, pushing the weight from your chest up toward the ceiling), and the squat (squatting down to the floor to a point of your knees reaching a minimum of a 90° angle, but sometimes beyond – considered an ‘ass-to-grass’ approach).

Powerlifting is likely the most popular method of strength training, as divided through the 3 aforementioned lifts, every muscle in the body is utilized and conditioned. Olympic lifting and Strongman training are beginning to gain more attention and traction in the public eye, but remain quite niche variations of strength training, as usually the equipment and facilities required to train in these ways are quite a bit more rare than your run-of-the-mill weight room – especially in the case of Strongman. In a word, strength training is about performance and output.

Read more on how to get strong with just 5 lifts here.

Bodybuilding

“You don’t really see a muscle as a part of you, in a way. You see it as a thing. You look at it as a thing and you say well this thing has to be built a little longer, the bicep has to be longer; or the tricep has to be thicker here in the elbow area. And you look at it and it doesn’t even seem to belong to you. Like a sculpture. Then after looking at it a sculptor goes in with his thing and works a little bit, and you do maybe then some extra forced reps to get this lower part out. You form it. Just like a sculpture.”

-Arnold Schwarzenegger, 7 time Mr. Olympia

Bodybuilding in its simplest terms is about sculpting the body to one’s desired aesthetic condition. The judges of bodybuilding competitions, in their various categories, look for things like overall muscle development/size, conditioning (vascularity and body fat percentage), and symmetry. At the top levels a lot of these factors come down to genetics, but nonetheless, everyone with bodybuilding goals both advanced and novice adheres to similar principles and chases similar goals (of various degrees, of course; not everyone wants to look like Ronnie Coleman.) Bodybuilding then, is primarily concerned with how one looks aesthetically, as opposed to how one physically performs. Put another way, if you can only bench press 50lbs but look better developed and more symmetrical than the guy beside you who benches 300lbs, you would still be crowned the winner from a bodybuilding perspective.

To achieve the desired goal in this sport, bodybuilders train differently than strength trainers. As mentioned, strength athletes are primarily concerned with the 3 major lifts mentioned above. Those lifts were referred to as “compound lifts” because they required multiple muscle groups in order to complete the lifts. In the case of bodybuilding, more often than not, athletes will segregate and compartmentalize their training so as to emphasize the training of particular groups, and sometimes particular individual muscles themselves. The prime example is probably a bicep curl. When performing standard bicep curl – assuming you are executing the lift with ideal form – your body remains entirely stable and static, while there is only flexion at the elbow, moving the weight from by your side, to parallel with the floor and back down again.

Endurance Training

While endurance training doesn’t preclude the athlete from any specific lifts, this type of training does, however, put an emphasis on shorter rest periods between sets, and often encourages much higher repetitions per set (reps) than the other two training style counterparts. Oftentimes, these rep ranges will exceed 15 repetitions per set and tend to act as a hybrid between aerobic and anaerobic exercise. Typically, these training sessions take the shape of circuit training, where an athlete will rotate quickly between a host of different exercises before taking a short rest. The most popular form of this type of exercise is likely CrossFit. In CrossFit competitions, athletes are evaluated on their ability to perform lengthy sets of exercises, before quickly moving onto another exercise. It is not unusual for higher-level competitions to demand 150 pull ups of an athlete before they move onto 1000 sit-ups/crunches. The athlete to perform these moves the quickest and with proper form, is declared the winner.

This brings us now to the science behind the different types of training and their associated rep ranges. Thus, we now jump into a crucial muscular distinction:

Sarcoplasmic VS. Myofibrillar Hypertrophy

First off, some vocabulary. Hypertrophy (pronounced hai per truh fee) simply means the ‘growing’ or ‘gaining’ of. So, when we talk about hypertrophy regarding muscle, we are simply saying the building of muscle. (For those interested, atrophy is the scientific opposite of hypertrophy – the ‘decaying’ or ‘losing’ of.)

As you can see above, the body is capable of developing in different ways depending on which way you train it. While some people are genetically predisposed to being more responsive to some types of training than others (fast-twitch vs slow-twitch muscle fibers, article found HERE), a healthy body will still adapt to the kind of stress under which it is placed. Enter the distinction between sarcoplasmic gains and myofibrillar gains.

To start, sarcoplasmic hypertrophy is essentially when the fibers within a muscle actually expand. By applying what is considered to be a medium amount of time-under-tension (TUT) to a muscle, roughly 20-30 seconds (which translates to 8-12 repetitions of an exercise), we encourage sarcoplasmic muscle growth. In layman’s terms, when we do an exercise for roughly 20-30 seconds the body responds to this physiological stress by expanding the muscle fibers within the given muscle. Over time, the muscles of the body itself will grow in size as a response to the type of exercise you have performed. So bodybuilders, for example, usually will perform their exercises between 8-12 repetitions per set.

On the other hand, we have myofibrillar hypertrophy. In this type of growth, the fibers within a given area of a muscle do not actually expand much – at least nowhere near where they do in sarcoplasmic growth. Instead, the body responds to physiological stress by growing new fibers within the same amount of muscular real estate. This growth is encouraged with a TUT of 1-20 seconds and usually translates to 1-5 repetitions for most people performing most exercises. This type of growth is the goal for Powerlifters and explosive-movement performance athletes (think NFL offensive linemen). Right off the bat then, the science here busts the myth that big guys are all that strong, or small guys are all that weak, comparatively.

Now, even though these two types of hypertrophy are distinct, it’s important to note that they are not entirely separate. Of course, if you train in a weight room you will experience both types of growth, but depending on how you apply TUT, you will encourage one type of growth over the other. Muscular hypertrophy, after all, is just the body adapting to physiological stress in order to better handle that stress on a subsequent occasion.

Concentric & Eccentric

Two sides of the same coin, concentric and eccentric components of a lift (sometimes referred to as the positive and the negative, respectively) describe the part when you’re actually lifting the weight, and the part when you’re returning said weight to its starting position. While usually the concentric (positive) is emphasized in classic bodybuilding thought, the eccentric (negative) is equally, if not more important. Understand from the get-go that it is not just about lifting the weight off of the rack. It is also about lowering it back down with control. Oftentimes, when you have no more gas left in the tank to perform the concentric part of a lift, there is quite a bit left in the tank for the eccentric. Tragically, like the fat cap of a high-quality grass-finished striploin steak, the eccentric part of most lifts are often ignored. While this portion of the article is dedicated to drawing your attention to the importance of both sides to the hypertrophic equation, we will soon discuss how to utilize the eccentric part of a lift to improve your overall results in the gym.

Progressive Overload

Next up, we have arguably the most important principle when it comes to your muscle-building long-term. The principle of progressive overload. Put simply, the principle of progressive overload stipulates that as your body begins to adapt better and better to a continued stressor, the body will need to be exposed to greater and greater stress in order to continue its adaptation. Now, while this principle may seem obvious or somewhat too broad to apply obviously to how one trains, it actually informs us very well, in not just each and every workout, but also in each and every set or repetition. Let us explain how.

Let’s take bodybuilding for example. We mentioned earlier that for the kind of sarcoplasmic growth you want when pursuing bodybuilding endeavors, you want to train each exercise at roughly 8-12 repetitions. Here’s how you apply progressive overload to this system:

Let’s say you have decided to do each exercise for a total of 3 sets. Grab some weights and attempt to perform a given exercise for a set of 8. If on the first set you cannot reach 8, the weights are too heavy to achieve bodybuilding goals (for now). Move down a little lighter. Now, with your lighter weights, you hit 13. Those are too light, to stimulate the body into the zone you need it to be to build muscle the way you would like – okay, a little heavier. Now you have your goldilocks weights. You perform a set of 8 reps and do 3 sets of that. Each time you return to the gym, try and get to that 8-12 rep range. Eventually, you will hit 12 for each of your 3 sets for that exercise with the original weights you have selected. The next workout, it’ll be time to increase the resistance, and start back for 8 reps. Bam. Progressive overload achieved. This is an amazing way of intuitively making sure that your physique continues to progress over time.

It should be noted that instead of increasing weight, one could, in theory also increase the stress by other methods including but not limited to: decreasing rest time, increasing set count, etc. The takeaway message here though is that without the diligent application of the progressive overload principle, one is setting a predetermined cap for how far their otherwise potentially limitless progress could go.

Advanced Training Techniques

Now we will cover some more advanced training techniques so that you can have multiple tools in your arsenal to take your training beyond any plateaus, should you encounter any. While these techniques could be applied to any style of training mentioned throughout this article, they are derived from bodybuilding methods and thus are best applied to the pursuit of aesthetic hypertrophy.

Supersets → Super sets are essentially performing one exercise directly after another without any rest between the two exercises. While oftentimes supersets are used to attack the same muscle from different angles (bench press followed by cable flye, for example), this technique can also be used with different muscles (bench press, followed by bent-over row). There are a few different benefits to the superset. First of all, they can drastically cut down the time you’re actually in the gym, as you’re essentially training faster. Second, supersets allow you to exhaust the muscle in a new way that can lead to stimulating the muscle into new, otherwise unyielded growth. As Arnie says “bodybuilding is a game of angles.” In other words, hit a muscle from lots of different angles to ensure you cause all the fibers within said muscle to truly activate.

Note: When supersetting, it is usually a bad idea to follow any compound exercise with an isolation exercise that is being used in the preceding compound movement (unless the primary and secondary exercises mainly target the same muscle). As an explanation of what we mean here, suppose you’re doing a military press (hoisting a barbell above your head and returning it to about neck level). A military press recruits primarily your deltoids, your upper pectorals, and your triceps. If your secondary lift – which again, is performed directly after the first movement without any rest – is a tricep extension, sure, you may get a great workout on your triceps, but now you are taxing one particular muscle in your compound military press, more than the others. When your next set roles around, you won’t be able to get the same exertion on your deltoid and upper pectorals because the third and supporting muscle of that lift, the triceps, cannot pull their weight (pun intended). Remember then, that if your workout is going to be composed primarily of supersets, which some people enjoy, be wary of which move you select as your primary, and which move you select as your secondary.

Dropsets → Dropsets are similar to supersets in the sense that one exercise is immediately followed by another. The difference though, is that instead of the initial exercise being followed by a different one, it is followed by the same exercise, but at a lower weight. The goal of this is to allow the body to push slightly beyond its maximum load by making the exercise easier as the load becomes more challenging to lift. Oftentimes, this takes the shape of the following: A set of 12 hamstring curl repetitions at 100lbs, immediately dropped down to 40lbs for another 5 repetitions. Note that how low you decrease the weight and how many reps you perform once the weight is decreased depends on you; there is no one size fits all, and this will likely change slightly from day to day.

Note: Dropsets can be dropped more than once. Oftentimes when it is the final set of an exercise, to ensure complete exhaustion, we will drop weight 3-5 times (100lbs, 60lbs, 35lbs, 20lbs, etc.) Keep in mind, however, that this is best performed as the final set of an exercise and probably only if that’s your final exercise for that entire muscle group of the day. As intended, dropsets can be very taxing and therefore your ability to perform another set at maximum output without an unreasonable amount of rest, is slim to none. We suggest keeping dropsets as your final K.O. punch to the muscle you’re training.

Pre-exhaustion → Suppose you are training your legs but your quadriceps are quite a bit more developed than your hamstrings (as is the case with most people, especially novices). If you go and perform a squat or some walking lunges, your quads take most of the load and will continue to grow at a rate faster than your hamstrings, which will obviously exacerbate the muscular discrepancy. Now, to begin this may not seem like much of a big deal, but over time, this can lead to a real headache and potentially injury, especially if you have several years under your belt of over stimulating your quads and under stimulating your hamstrings. Introducing the pre-exhaustion technique. Popularized by Scharzenegger himself, the pre-exhaustion technique calls for the athlete to perform a few sets of isolation exercises related to the overbearing muscle, so as to, well, pre-exhaust it. While performing isolation movements before compound ones is something of a taboo in bodybuilding, what we are essentially doing here is leveling the playing field so as to encourage equal development within muscle groups. In the long run, this technique can save you much frustration, as the longer you leave a discrepancy of this sort, the harder it becomes to rectify.

Forced Negatives/Cheat Reps → Forced negatives are great, but usually require a training partner. Cheat reps on the other hand, can usually be performed solo, but are limited to the exercises with which they can be performed. To start, a forced negative refers to the distinction we made earlier regarding concentric and eccentric components of an exercise. Basically, when your body’s concentric ability is taxed (the ability to move the weight from its starting position to its goal position), that doesn’t necessarily mean the eccentric portion is also finished. So, in order to tax both sides of the coin properly, a training partner can assist you to lift the weight, and then you perform a slow eccentric, lowering of the weight to its starting position. Similarly to the dropset, this technique allows the athlete to train, in some sense, past failure.

Conversely, cheat reps allow yourself to ignore strict form on the eccentric and “cheat” the weight to its top position, so as to allow the athlete to return it slowly to its starting position. For example, imagine someone using their hips and legs in a bicep curl in order to generate enough momentum to get the bar to the top of the movement (bicep fully contracted), and then they lower it back down slowly.

Now you have, at your disposal, a few classic techniques that even the best of the best have used in order to take their physiques to the next level. We will now be moving onto one final but incredibly important concept to understand…

Mind-Muscle Connection

As the name suggests, the mind muscle connection comes from one’s ability to control a muscle on the body without the need, necessarily, for physical stimulus. When you perform a kegel exercise at will, that is mind-muscle connection. When a pro bodybuilder is posing their perfectly symmetrical physique standing out on that stage, they are displaying mind-muscle connection. And when Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson inevitably bounces his pecs repeatedly in whatever “fun-for-the-whole-family” movie he finds himself in that year, that is mind-muscle connection…

While it may seem like it’s not a big deal to be able to control your muscles at will like that, we assure you that it really is. The reason for this is that if you can control your muscles at will, in combination with lifting heavier and heavier weights, you are forcing your body to contract the muscles you want to develop. Our bodies were not evolutionarily made to require huge trapezius muscles or bulging biceps. Instead, our bodies are purpose oriented. They are mainly concerned with moving a weight from A to B, not ensuring that all 3 heads of our tricep are developed as aesthetically as possible. For this reason, we need to learn how to use our body differently. Admittedly, this comes with time. After you begin you lift weights for a few months, and maybe a few years, you will become more in tune with which muscles ought to be doing what in a given lift. As such, you will be rewarded with better and better contractions, leading to better and better development. We can tell you from experience that you do not want your posterior deltoids doing most of the brunt work when you are doing a bench press to develop your chest. This comes from mind-muscle connection. The same way that your mind develops habits over time, your body will too. This means, unfortunately, that if you get in the habit of lifting a weight a certain way, it is incredibly difficult to reverse this process – we’re talking years and decades here, people.

Author’s Motivation

I’ve loved fitness and bodybuilding ever since my uncle took me to the gym for the first time at 13 years old and my mother bought me Arnie’s Bodybuilding Encyclopedia. Despite telling myself I will experiment with different kinds of weightlifting in the future, bodybuilding, the theory behind it and in practice will always be my first love. While I partook in American football, and boxing for years, bodybuilding captured me in a unique way. The thing about it is, if you want to be the best, it consumes you 24/7. You cannot miss a workout, because your competition isn’t. You cannot cheat on your diet, because one day of cheating can require weeks of repair work – especially if you are in the single digits percentages in terms of body fat. Additionally you cannot hide your weaknesses – you cannot have any weaknesses. You cannot live off your jab, because your hook is mediocre. When you step on stage, you are there for people to evaluate literally every single thing they see and compare you to a bunch of other dudes (or women), who have the exact same goal as yourself. In any case, throughout my research, I’ve had the good fortune of coming across amazing people with amazing techniques and practices. Some of these practices, I have shared here with you today in hope that they can serve you as they have served me.

Conclusion

There are several ways of approaching the weight room or gym. Luckily, kinesiology and the science of developing the musculature and performance of the human body as one sees fit takes routine and exponential steps, which allows even noobiest of novices to understand the principles involved with their journey and goals. Whether you prefer strength, aesthetics, or endurance, the weight room can offer you a lifestyle where you gain access to seeing the continual growth and progress of the one machine you get to drive around until your final day, your body. We encourage you to apply the techniques we shared, to wherever your fitness goals may take you and hope that they can have positive impacts on their attainment.

Best of luck biohacker, and as always, keep moving UpRiver.